Immigrant Tales | Sugarcane, Segregation and Snake Infested Fields

06/18/2016By: Monica Victor

Tale of a West Indian Sugarcane Worker in the ’60s

On February 28th, 2014, Morrison James flew from Vieux-Fort to Miami. It was his first flight to Florida in 49 years.

“How was your flight Dada?” we asked. He recounted a moment on the plane.

“The flight attendant asked if I wanted a snack,” he recalls. “’No, thank you,’ I said – I have no teeth!” James smiled as he spoke, revealing less than a half-dozen he’s held onto.

When James was 25 years old, he had all 32s in his mouth and was looking forward to his first trip to the states. That was 1965, the same year the EC$ began circulating in St. Lucia, replacing the British West Indies dollar. It was also a time when young West Indian men were “chosen” to go overseas to “cut cane.”

But the selection process wasn’t easy. It involved blood tests and background checks. Applicants had to be in tip-top shape, drug-free with a squeaky clean record…

James took a shot and applied

While listening to the radio one day James heard that recruiters would be in his neck of woods to scout young men interested in going to America to cut cane. At the time he worked in construction but he made himself available that day. James met the height and weight requirements and so he was handed a card to go get his blood work done. Soon thereafter the results were in, and James and countless other young men from across St.Lucia were on a flight to Florida.

Being selected was a huge deal. Family members and friends often gathered in the ‘yard’ anxiously awaiting the news of whether their loved one made the cut or not.

“Mwen fè’y” (I made it) those selected would say. Or, “Mar fè’y coo sala. San mwen pa té bon,’ as they would say in our local parlance.(I didn’t make it this time, my blood work wasn’t good),” said the unlucky ones. For those who were not selected, often a lack of potassium was to blame and the prescription to make their blood ‘good’ again was to eat lots of green bananas and spinach among other things. But James didn’t have to take those measures because his blood was ‘good’.

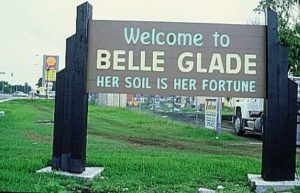

Leaving behind his girlfriend and two kids, James made the trip to Belle Glade to assume his duties as a migrant sugarcane worker.

Life in the barracks…

“We were paid US $400. In today’s dollars it may not seem like much but back then it was a lot of money,” he says. “We were given an allowance and the rest of the money was sent to our bank accounts at home.”

James said the forced savings was a way to make sure they had money when their contract ended and that their dependents were taken care of.

And although second and third jobs were not allowed, special privileges were given to ‘good’ workers to work on other fields. James earned that privilege but that was after getting caught sneaking out to another job.

“The Super noticed that I was gone every weekend so he decided to wait for me around the building one morning,” he remembers. “But, I had been working on that other job for about two months already.”

“Where are you going?” the Super asked me.

“To work,” I said. ‘He didn’t like us working for other companies.’

“Let’s go back. Come over here, make some breakfast,” he said to me as he opened up the kitchen. “And from now on let me know when you’re going.”

James earned special privileges not only because he was a good worker but because, well…

“I had a bunch of family photos in my wallet. Among them was a photo of one of my sisters who lived in Barbados at the time. The Super saw the photo and fell in love,” James chuckles.

So James worked two other jobs harvesting celery, corn and peanuts on the weekends, even in snake infested fields.

“We were paid $0.50 cents for the first couple of hampers. The others would be $0.75 cents and $1.00 for the last one. The plantations were infested with snakes but we were only allowed to kill the rattle snakes,” he recalls. “When the snakes saw us they’d hiss away except for the rattle snakes.”

James never got bit but he didn’t always feel well. He recounts when illness kept him from working.

“I needed clearance to go back to the fields, but my Super wouldn’t let me. He said I wasn’t well enough. I told him that I needed money to feed my children. And within two days as opposed to several days I was given my money, and was told I could go back to work.”

James said it was a no work, no pay policy. And with mouths to feed and the ultimate sacrifice to fulfill, he reported back to work and worked every day until his contract ended and returned home.

Now almost 50 years later, he was back on American soil

On January 28th 2014, James turned 75. To celebrate, his three youngest daughters and granddaughter thought a trip to Florida would be ideal. He accepted our invitation this time.

Once a vibrant youth and efficient sugarcane cutter, he now struggles to climb the stairs due to the arthritis or (‘afferitis’ as he calls it) in his knees – his salt and peppered hair and receding hairline signifying wisdom gained as they say, and indicating the loss of youth. He was in America again. But one thing remained unchanged – his memories of Belle Glade.

About a week into what we thought would’ve been a six month stay, it was time to re-visit old memories and create new ones.

“Dada, would you like to go to Belle Glade to visit the sugarcane plantation?”

“Awa,” (‘not really or no’),” he responded.

Awa to Belle Glade?! A place that came up in every conversation and he didn’t care to go?

But this was our house and what we say go, so we are going to Belle Glade (lol).

It was a Sunday morning, a bright and beautiful day in Sunny Florida, perfect, just perfect for a road trip. We all jumped in that SUV and off we went to embark on the less than two hour expedition with our dad. The first hour into the journey was pretty quiet but that would soon change. Once we ventured into familiar territory and he saw sugarcane fields and recognized street names, he came alive!

Gazing out the window, pointing and lifting from his seat at times, James recounted life as a sugarcane cutter…

“Along the canal was the hardest to harvest,” he remembers. “And whoever worked there would get paid more money. Each person was given two rows of sugarcane to cut and was paid $50 per row. If you didn’t finish your rows you didn’t get all your money.”

And even though the place had changed quite a bit he recognized the routes and street names…

“This area was called South Bay. Thieves often lurked here to rob unsuspecting migrant workers. But I never got robbed,” he says. “We’d go to the Royal Store and Consignment Store to buy clothes. Men’s suits were $5 and work clothes $1. Lee jeans were $5 and Wrangler was $ 2.50.”

They ate three meals a day neither of which was St. Lucia’s National Dish green fig and saltfish…

“We grew tired of eating rice day in and day out. So, in between meals we’d often steal sugar to make sweet water to eat with crackers and cake.”

And even when their palettes craved for something more scrumptious, they couldn’t just walk into any café to satiate their cravings.

And even when their palettes craved for something more scrumptious, they couldn’t just walk into any café to satiate their cravings.

Because it was 1965 – a time when skin color dictated where you were welcome and where you weren’t…

“There were two camps, one for the whites and one for the colored. Whites were allowed near the black camp but the blacks couldn’t dare venture into the white camp,” he recalls.

“We were not allowed a table at the cafés and restaurants and sometimes they wouldn’t even let us in. And, if they did decide to serve us it was always takeout. Some would serve us, refuse our money and hurry us out of there.”

But times have changed. And the efforts of activists like Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks are now more evident…

While in Belle Glade we stopped at a playground so his 3 year old granddaughter could play a while. Then we stopped at Lake Okeechobee a place he and his comrades frequented. About three hours later we left Belle Glade and headed back home.

But, there was at least one more stop to be made…

About 30 miles from Belle Glade, we were now in Wellington. We spotted a shopping center that housed numerous restaurants and shops. For some reason we agreed to dine at Carrabas restaurant closest to the highway. With a welcoming smile and a friendly disposition the hostess (Caucasian/white) escorted us (black/colored as my dad, a product of the 60’s would say) to a table.

“Can I get you guys anything to drink?” she asked.

“Water, please,” James responded. She continued around the table taking our orders.

“Ready to order?” she later asked.

“I’ll have the salmon and mashed potatoes,” James ordered.

And much like all the other patrons – a diverse group might I add – James sat to partake of his meal until he was done (and… yes they accepted our money lol).

I didn’t ask him how that felt. In fact I didn’t have to. The look on his face conveyed content, happiness and gratitude. We and [him] will forever be grateful that he made that trip. Witnessing our dad get excited about the place he once labored long before any of us were born was simply sublime.

Although we had hoped that he would spend at least 6 months with us, two months into his vacation he was ready to go back to St. Lucia. There is no doubt that he loves us dearly and if he could be in two places at once he would. But, he is an islander, an older island guy used to having windows and doors open with fresh sea breeze all day long. And here, being cooped up in a locked house idle just wasn’t for him.

“I have to go take care of my garden,” he often said. His yam and plantains and even sugarcane. “I don’t like being in a closed house doing nothing.”

One year later, tragedy struck and James had to make the trip again…

Fast forward to March 2015 and James would find himself traveling from Vieux-Fort to Miami again. Not to cut cane or celebrate his birthday this time, but to celebrate life, the life of his youngest offspring whose life was cut short by this darn Lupus. Lupus stole her from us. She was only 30 years old.

The stories of moms and dads, uncles and aunts, grandpas and grandmas immigrating are abundant and their experiences perhaps similar. When they weren’t en route to the sugarcane fields they were traveling to reunite with relatives or friends who paved the way for them. Often taking jobs albeit unattractive paid the bills and took care of the family they left behind.

While we received the barrels and new clothes and perhaps a transistor radio (every cane worker came back home with a radio–lol), the experience on the field was either poignant, pleasant or both. And for this West Indian sugarcane cutter, Morrison James, it was both.

Everyone has a story, what’s yours?

About the Author:

Monica Victor is the executive producer of Manmay LaKay Magazine. She’s a copywriter, social media and reputations manager at a financial services company. Her writings there aim to help folks make good use of their dollars and sense. Her writings at Manmay LaKay Magazine seek to celebrate her fellow St.Lucians, empower and inspire folks to live their dream, raise awareness on the diseases that afflict us, connect all St.Lucians globally and to keep her St.Lucian heritage alive.

Monica Victor is the executive producer of Manmay LaKay Magazine. She’s a copywriter, social media and reputations manager at a financial services company. Her writings there aim to help folks make good use of their dollars and sense. Her writings at Manmay LaKay Magazine seek to celebrate her fellow St.Lucians, empower and inspire folks to live their dream, raise awareness on the diseases that afflict us, connect all St.Lucians globally and to keep her St.Lucian heritage alive.

Connect with Monica:

Email: monae76@gmail.com or stlucianpeople@gmail.com.

Like Manmay LaKay Magazine on Facebook

Follow Manmay LaKay Magazine on Twitter @stlucianpeople and on Instagram@stlucianpeople

Connect with us at stlucianpeople@gmail.com, Manmay LaKay Facebook, StLucianpeople on Instagram and Twitter.